Choosing Sides

Even half-finished literature speaks uniquely to every reader. Harper Lee speaks directly to me

The newly-published Go Set a Watchman is really just one long set-up to create a confrontation between Jean Louise (the grown-up Scout Finch) and Atticus — no longer the saint of To Kill a Mockingbird but an apologist for racism. Only now, after their deaths, do I realize that I desperately need the same act of separation from my parents that Scout passes through in the climax of Watchman.

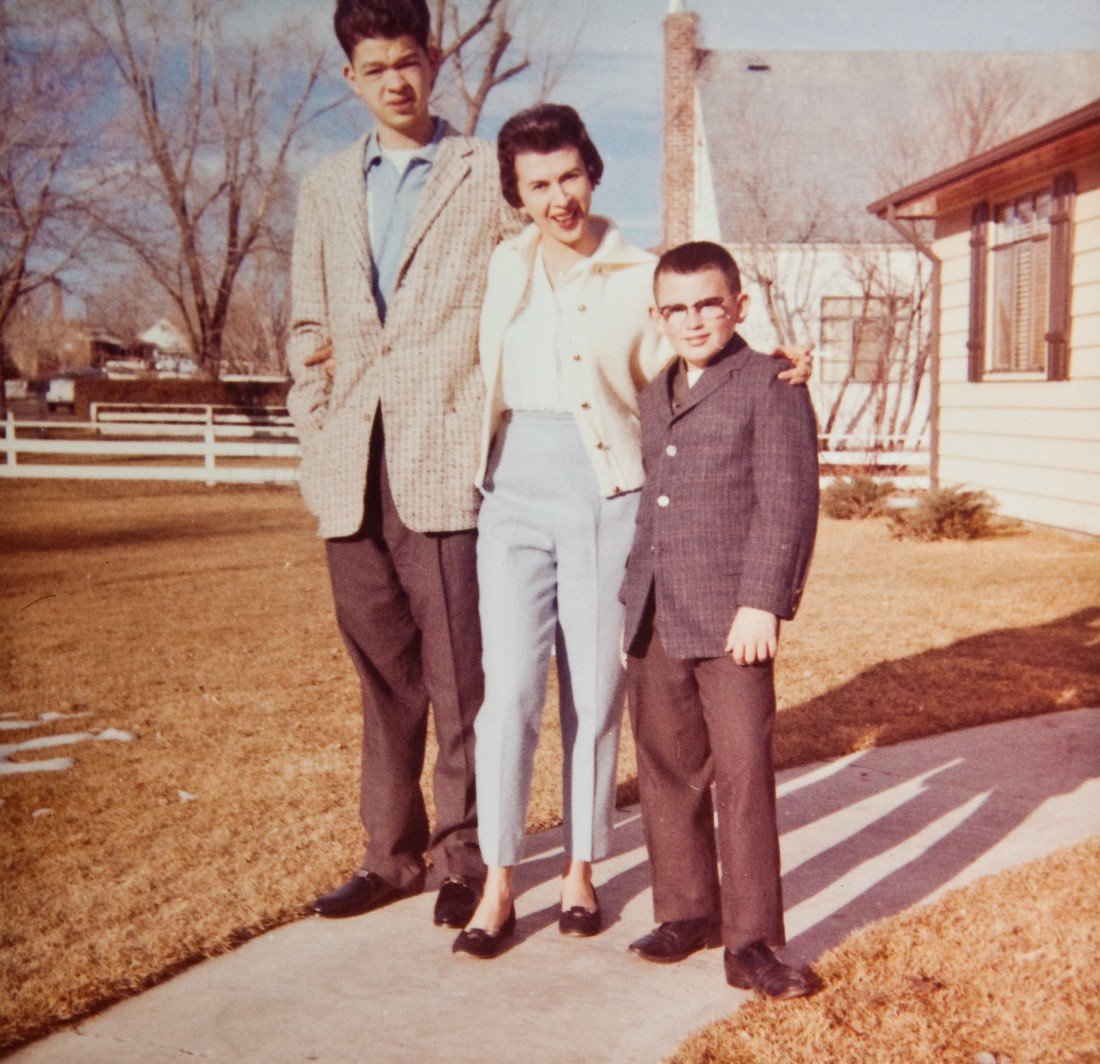

My family conflict centered on my mentally ill brother. I’m two drafts into a memoir about his life. My readers keep pushing me: “How did YOU feel? Find YOUR emotions. REACT to your brother’s story of madness, to your mother’s sorrow and guilt.” I’ve had a terribly difficult time responding.

My wife, Joanne, reading draft after draft, urges me to replace all those “we”s with “I.” She says, with exasperation, “This book is not about ‘we.’ It’s about you!”

I’ve kept saying, “But that’s how my parents and I felt! It’s a family story.” But in one conversation, I finally got it. Joanne said, “Your parents could have written this. You weren’t Mike’s parent; you were his brother! How did you feel?”

My forthright spouse pushed me to this flash of insight just as I finished Go Set a Watchman.

The Finch family conflict hinges on race. Jean Louise’s moral anchor — her father — reveals himself to be complicated and imperfect. She’s shattered. She confronts Atticus, storms out, and packs her bags — but her uncle turns up at this critical moment.

Uncle Jack tells Jean Louise that only when she stood up to her father could she progress from being “an emotional cripple, leaning on him, getting all the answers from him, assuming that your answers would always be his answers.” And so her father and her uncle are grateful for the confrontation; they’re relieved. Scout now can set her own “watchman,” live by her own conscience, her own morality, not Atticus’s.

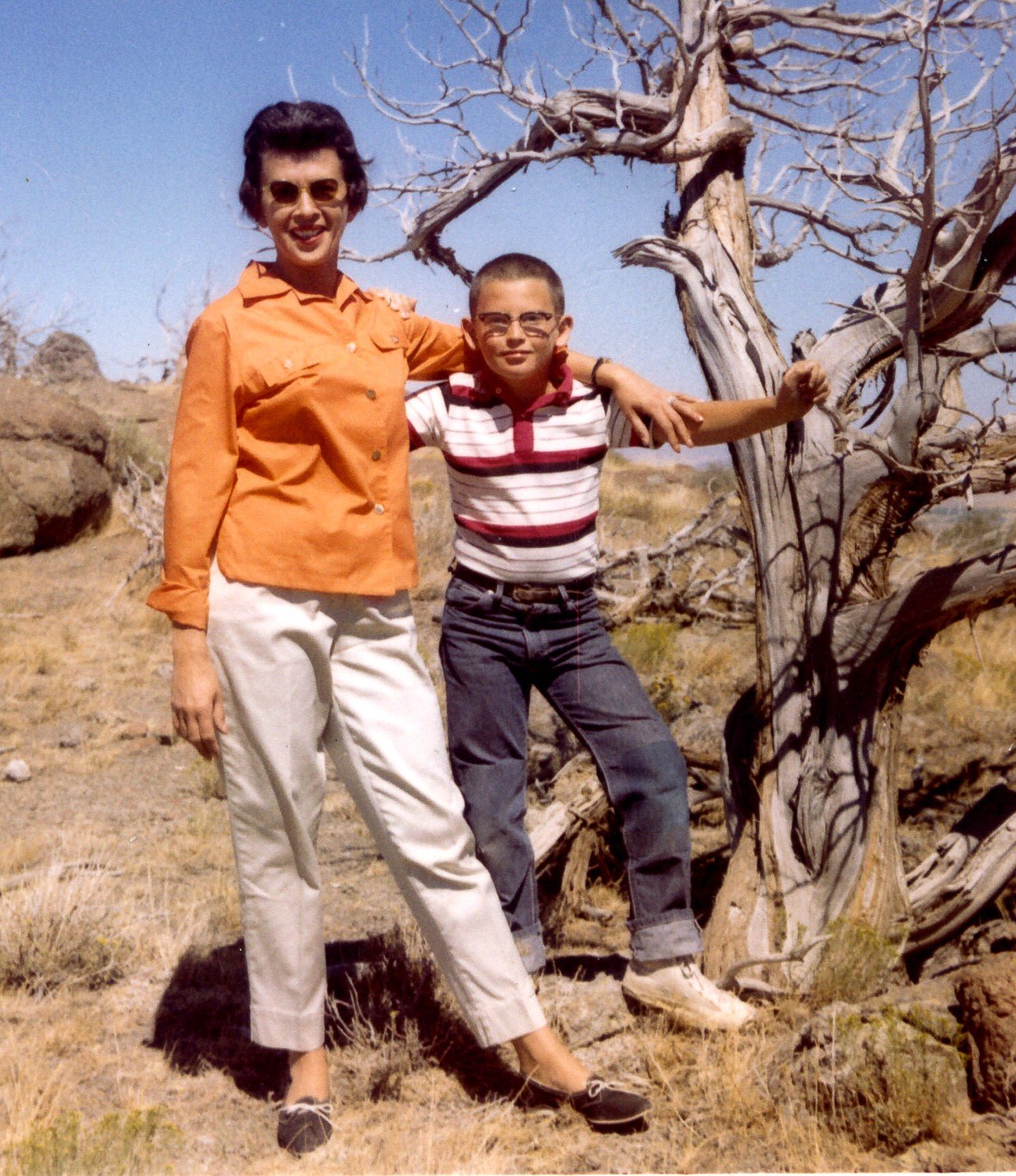

Jean Louise had attached her “conscience” to her father “like a barnacle.” My connection to my parents was nearly as tight. All my life, I’ve repeated the platitudes of our Family Myth: my brother Mike was brain-damaged at birth; he was swept away by paranoia at 14; we had no choice but to commit him to the state hospital; he rejected us when he emerged from institutional treatment ten years later, and we didn’t speak again during the ten years remaining before his death. His path was inevitable.

I’ve been striving to articulate my emotional reactions to Mike’s story without ever separating myself from my parents’ emotions. I was the good son, a balm to replace the sorrows of the tragic son. Mom and Dad protected me from my brother’s harrowing tale — and I protected them by never challenging their explanations and rationalizations. I accepted my parents’ version of Mike, and I never questioned that story.

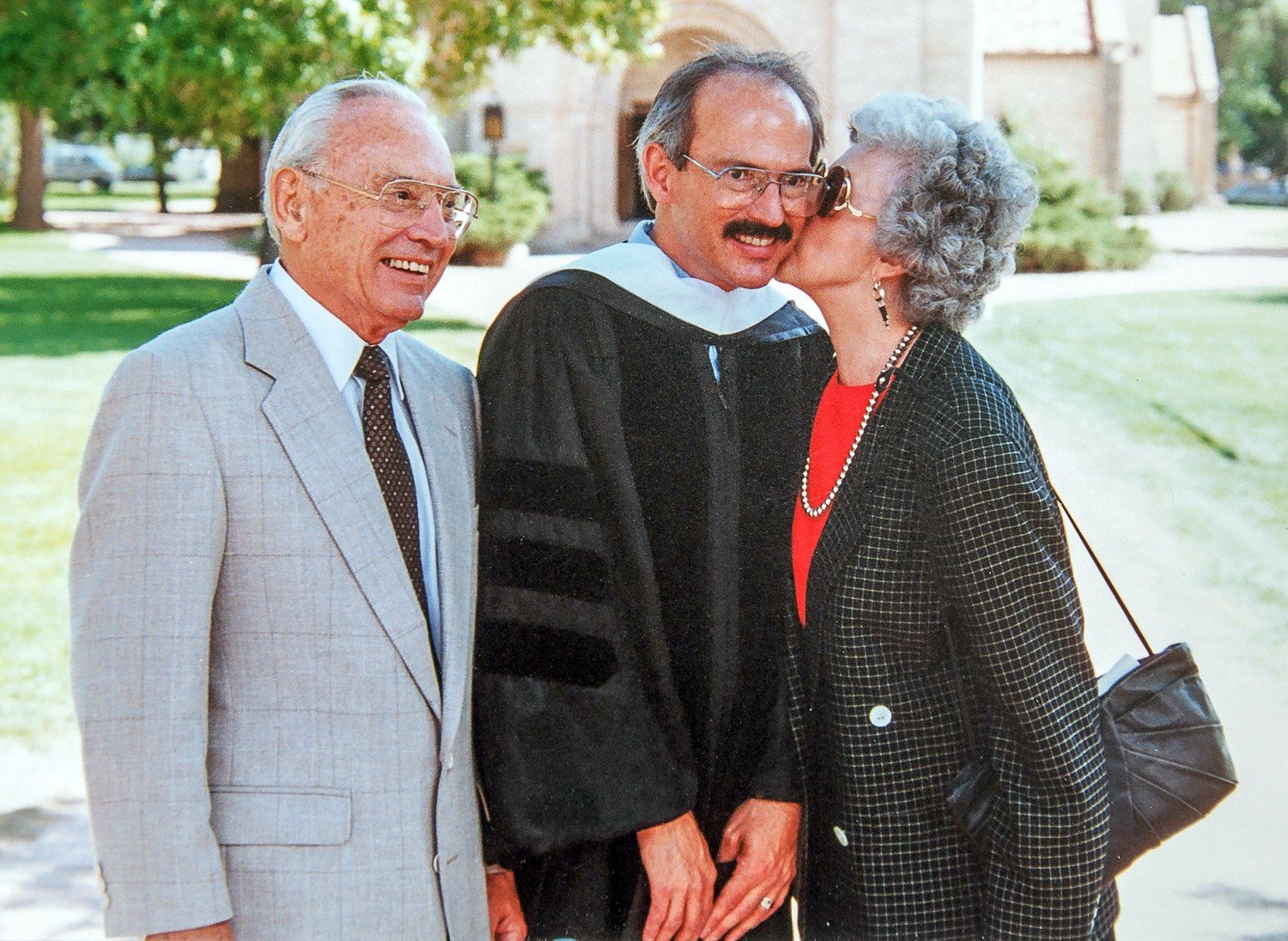

Now, years after they’ve died, I find myself working to at last stand apart from my parents. I’ll remain tender about my lifelong closeness with them, but like Scout, I also need to function “as a separate entity” more than I ever knew.

How do I feel? Well, let me tell you…

Stephen Trimble will post stories on Medium as he works on his memoir, Leave Me Alone Forever: My Brother’s Madness, My Mother’s Sorrow. Steve’s website is: www.stephentrimble.net.